Read this story in Nepali: अपारदर्शी दल : करोडौँ खर्च, देखावटी चन्दा

The Nepal Investigative Multimedia Journalism Network (NIMJN) revealed last August that political parties had evaded taxes and disclosed statements of income and expenditure that were lower than the actual figures. In this investigation, we have exposed the lack of transparency within the donations raised by political parties. The donations raised by the parties are known only to the giver and the receiver; they never make public the name of the individual or the amount of the donation taken from them. However, the law stipulates that donations over 25,000 rupees must be transacted using a banking check or transfer, and the name, address, profession, and source of income of the individual giving more than 100,000 rupees must be disclosed. Despite this, the parties are conducting their financial transactions by violating this legal provision.

... ...

How much money do you think the political parties collected in donations during the year 2079 (2022) local level elections and the House of Representatives and Provincial Assembly elections?

Your guess might be nowhere close. This is because the then-CPN (Maoist Centre) submitted details to the Election Commission stating that it collected only 50,000 rupees in donations for the local level elections and 10,000 rupees for the House of Representatives election.

Your guess might be nowhere close. This is because the then-CPN (Maoist Centre) submitted details to the Election Commission stating that it collected only 50,000 rupees in donations for the local level elections and 10,000 rupees for the House of Representatives election.

The Nepali Congress collected 93.3 million rupees, the CPN (UML) collected 68.4 million rupees, and the Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP) collected 18.6 million rupees in donations during the year these elections took place. However, they have not mentioned who gave the donations.

In the annual audit report for the fiscal year 2079/80 (2022/2023), when the House of Representatives and Provincial Assembly elections were held, the Maoist party reported collecting only 10,000 rupees in total donations. Before that, in the fiscal year 2078/79 (2021/2022), when the local elections were held, it showed that it had collected only 50,000 rupees from Arghakhanchi Cement as institutional donations. The local level election was held on Baishakh 30, 2079 (May 13, 2022), and the House of Representatives and Provincial Assembly elections were held on Mangsir 4, 2079 (November 20, 2022).

If one recalls the campaigning, the expenses incurred by candidates, and the spectacle displayed by the Maoist party during the local-level elections, as well as the Provincial and House of Representatives elections, it is difficult for anyone to believe that they received only 60,000 rupees in donations.

A top-level leader (who did not wish to be named) of the then-Maoist party also stated that the donation amount was much higher than that. “A lot of donations were collected,” the leader said, “I am also surprised now that you mention it, as to why only that much was shown at the time.”

Ganesh Man Pun, who took charge as the party's General Secretary six months ago, also suggests that the reality would be known only to those who handled the transactions at the time. “The Maoist party does not usually collect donations at the central level; the reality might be just that,” he said. “The friends who handled the transactions at that time would know the truth. I only started working six months ago.”

The Maoist party is not the only party that does not submit details of its actual income and expenditure, fails to keep records of donors as per the law, and shows a small amount of donations despite receiving much more. The list includes almost all parties, including the Nepali Congress, CPN (UML), RSP (Rastriya Swatantra Party), and CPN (Unified Socialist).

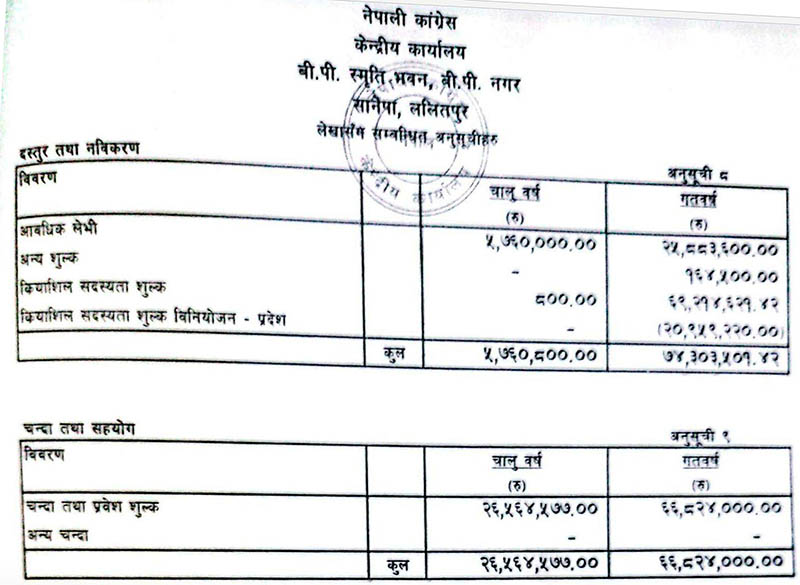

The Nepali Congress submitted details to the Commission showing that it collected 26 million 564,000 rupees in donations during the fiscal year when the House of Representatives and Provincial Assembly elections were held, and 66 million 824,000 rupees in the previous year of the local level elections.

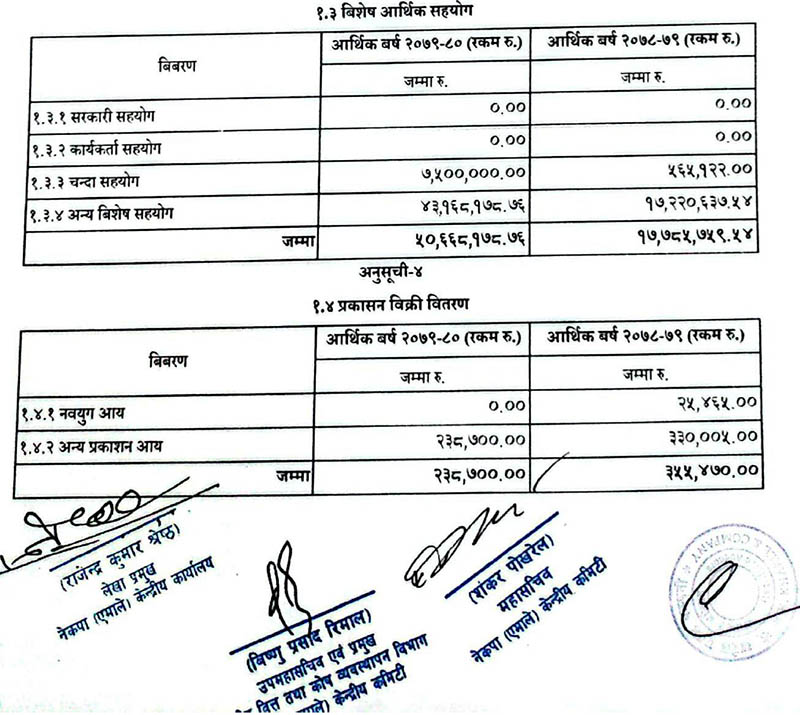

It is seen that the CPN (UML) collected a total of 50 million 668,000 rupees in donations during the fiscal year of the House of Representatives election, which includes 7.5 million rupees under the heading of special financial support and 43 million 168,000 rupees under the heading of other special support. It submitted details showing that it collected 17 million 785,000 rupees in donations during the fiscal year in which the local-level elections took place.

The Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP) submitted details to the Election Commission showing that it collected 18 million 625,835 rupees in individual donations domestically during the year of the representative elections. The RSP did not participate in the local-level elections or the Provincial Assembly elections.

Who are the donors that gave 93.3 million rupees to the Nepali Congress, 68.4 million rupees to the UML, and 18.6 million rupees to the RSP in these two elections? Neither the Election Commission knows nor do the parties wish to disclose.

The report submitted by these parties to the Election Commission only includes the figures of the collected donations in millions. The names and details of who gave how much money are not included. Even when contacting the person responsible for the party's accounting system to request the details, they were unwilling to provide them. So much so that when asked for a reaction regarding the donors, they dodged the question by pointing fingers at one another.

Even though the amount collected by the parties under the donation heading is in the millions, the details do not include the name, address, or source of income of the donors. This is despite the law requiring that donations exceeding 25,000 rupees must be received via banking check or transfer, and the name, address, profession, and source of income of the individual donating more than 100,000 rupees must be disclosed.

Section 38 of the Political Parties Act, 2073, provides for parties to receive voluntary contributions. Sub-section 1 states that Nepali citizens or organized institutions may voluntarily provide financial assistance to a party. Sub-section 3 states that if a party receives financial assistance exceeding 25,000 rupees from any individual or organized institution, it must be received only through banking check or banking transfer.

Similarly, Rule 12 of the Political Parties Regulation, 2074, clearly mandates the disclosure of the source of financial assistance. When receiving assistance exceeding 100,000 rupees from any citizen or institution, the regulation requires that the name, surname, address, profession, Permanent Account Number (PAN) of the individual or institution providing the assistance, as well as the source of the donated amount, must be disclosed, and a record of such details must be maintained.

The outgoing Chief Election Commissioner, Dinesh Thapaliya, says, “Who gave the party how much donation? The report should come with the names of the donors, but that is also missing.” The parties also have no basis to claim that the names were not disclosed because the donors contributed less than 50,000 rupees.

Madan Krishna Sharma, the head of Transparency International Nepal, states that by not making the details of their actual income and expenditure public, the parties are defying the legal provisions and mocking good governance. “It is no secret that power and money are at play within the parties,” he said. “If we want good governance from the government, the first agenda must be to end the opaque activities of political parties.”

Parties disclose the amount, but not the donors

The Congress, which collected 93.3 million rupees in donations, did not want to disclose the details of the donors. Krishna Paudel, the Chief Secretary of Congress, said, “Whatever the reality is, it is all in the report itself.”

Just like the Congress, the UML also has not disclosed the details of its donors. Dr. Pushpa Kandel, the Chairman of the UML's Central Accounts Commission, also did not want to make the donors' names public. Claiming that the party's actual income and expenditure were put in the report, he said, “If the accounts had been manipulated, no questions would have been raised. Since we put what was real, questions might have arisen.”

The RSP showed that it spent money even though it reported collecting only 290,000 rupees in donations during the year of the local-level election.

For the year of the House of Representatives election, the RSP reported collecting 18.6 million rupees in donations but showed election expenses of only 1.577 million. It has also not made public the precise details of who gave how much assistance.

Abhishek Ghimire, the head of the RSP's Accounts Commission, stated that the names were not made public because no one contributed more than 100,000 rupees.

The Janata Samajwadi Party also did not show the details of its donors. It showed that it collected 434,000 rupees in donations in the fiscal year 2078/79 (2021/2022) and 300,000 rupees in 2079/80 (2022/2023). However, the expenditure was shown as double the donation, at 821,000 rupees, and 2.771 million rupees for the House of Representatives election.

Meanwhile, the then-CPN (Unified Socialist) and RPP (Rastriya Prajatantra Party) have partially disclosed the details of their donors in their audit reports.

The RPP's audit report mentions that it collected 15 million 551,000 rupees in donations during the fiscal year 2079/80 (2022/2023), when the House of Representatives and Provincial Assembly elections were held. The report shows that Pashupati Shumsher JBR gave the largest donation to the RPP, contributing 4 million rupees.

The Unified Socialist, which won 10 seats in the House of Representatives, collected 52.5 million rupees under the donation heading for the local elections and 35 million 303,045 rupees in donations during the year of the Provincial Assembly and House of Representatives elections.

The report mentions that Kisan Shrestha donated 10 million rupees during the election period. Soma Pandey, a leader of the Unified Socialist, says, “Kisan gave 10 million, we also issued a receipt, and that is in the report itself.”

He stated that all assistance received by the party was transparent and that the details were submitted to the Commission in accordance with the law.

Accounting system of parties non-transparent

A team comprising the Director of the Auditor General's Office and four other auditors has also raised questions about the income and expenditure details of the political parties submitted to the Election Commission. The audit reports submitted by the parties have been examined by an expert team from the Auditor General's Office for the past three fiscal years. The expert team's report states: “Upon scrutiny of the income and expenditure statements, it was found that some parties’ auditors submitted reports without an opinion, transactions were not conducted through banks, bank balance certificates were not submitted at all, and bank balance proof differing from what was shown in the financial statements was presented.”

The Auditor General's team also concluded that if the weaknesses they pointed out were rectified, the financial transactions and status of the parties would become known, and it would help the parties maintain financial discipline.

The expert team of the Auditor General's Office studied the audit reports of 91 political parties for the fiscal year 2078/079 (2021/2022). Out of the 91 parties that submitted audit reports for 2078/79 (2021/2022), 48 parties did not even disclose their bank accounts.

The audit report conducted by the expert group for the Commission mentions that parties tend to superficially show only the details of the available balance amount in their audit reports.

Source of UML's income is political appointments

The legal provision allows political parties to show only membership fees, renewal fees, income from sales, interest, support received from members, and financial assistance as income. However, in the UML's audit report for 2078/79 (2021/2022), money received from political appointments was also shown as income. The amount under this heading is 2,531,560 rupees. The expert team deployed by the Auditor General's Office pointed out that this amount is irrelevant and should be controlled. The Auditor General's report states:

“The Election Commission should control such transactions.”

UML Vice-Chairman Yubaraj Gyawali, however, stated that the money under this heading was not taken separately for giving an appointment to an individual but was taken as a specific levy after a party member received an appointment. “Someone might have been appointed upon the party's recommendation, and they have to deposit a certain amount into the party's account. It is not that they submitted another amount just for getting the appointment,” he says. “If a party member gets an appointment, they have to deposit a certain percentage of their salary into the party's account. This same amount has been transparently included in the report. There is no need to doubt this.”

The report does not disclose who submitted this amount. He stated that just as MPs pay a certain percentage of their salary as a levy to the party, so do party workers who receive appointments.

Non-transparency is one cause of public dissent

Political parties and their leaders came under fire in the protest organized last Bhadra (September) by Gen Z youths, who were angered by the opaque activities and luxurious lifestyles of the political parties and their leaders. Not only were party offices targeted in the fervour of anger against political parties, but the houses of party leaders were also set on fire. The angry mob set fire to structures including the Parliament building, Singha Durbar, and the Supreme Court. This clearly shows the level of disillusionment the youth had with the parties.

Purushottam Yadav, a Gen Z leader, says that the non-transparent activities of the parties led to the protest on Bhadra 23 and 24 (September 8 and 9). “Individuals who were already prime ministers before I was born are still prime ministers today,” he says. “There is a share/division of power from the office that manages dead body funerals to the Prime Minister's office. The sentiments of the youth were never even attempted to be understood. Were we born to go and study abroad?”

He accuses the parties surrounding the government of not being transparent themselves and of trapping the country in a quagmire of corruption. He asks, “How are the parties operating? Where does their funding come from? How are they repaying the favors to the donors? They certainly don't have crowdfunding. Shouldn't the parties that govern the people be transparent themselves?”

He says that damaging the Parliament building, Singha Durbar, and private property in anger against the leaders was wrong.

Dipesh Ghimire, an associate professor at Tribhuvan University, also says that the country has reached its current state because the accounting of the income and expenditure of political parties is opaque.

“The collection of assistance and donations is not official. The expenses are also not organized. It is also not in the banking system,” he says. “Parties also fall under the definition of a public body. A party should make every piece of information public as per the requirements. However, the reality is hidden.”

He stated that the accounting system of the parties would not improve until there is a provision for their audit to be conducted by the Auditor General's Office. “Their income and expenditure are opaque. The Right to Information requires public disclosure every three months. Even when one asks for the expenditure and income of the parties, it is not provided,” he says. “The parties are currently facing the consequences of this.”

Weaknesses of the parties also visible in studies

Transparency International has concluded that financial opacity has increased in Nepal because political parties have violated the law. Its report, released in 2024, mentions that political parties are considered corrupt institutions in Nepal.

However, this is not the first time that reports from international organizations have identified Nepali political parties as corrupt institutions. Even in 2013, a Global Corruption Barometer study ranked political parties as the most corrupt institution, coming in at number one.

Based on the responses given by participants in that study, political parties were identified as corrupt institutions by 77 percent, civil servants by 66 percent, the police by 58 percent, the parliament and judiciary by 51 percent, and business/the private sector by 30 percent.

According to Transparency International, the main problem of political parties is the lack of financial transparency and accountability. The study suggests that parties must comply with the law to practice internal democratic governance, financial transparency, and accountability.

A study conducted by Purak Asia this year in Gandaki Province also showed a high graph of public dissatisfaction with political parties. The study mentions that the misuse of power, position, and authority by the political leadership is one reason for citizen dissatisfaction. Among the 1,067 respondents surveyed using random sampling, 89.5 percent expressed dissatisfaction, stating that the political leadership misuses power, position, and authority. Only 5.9 percent disagreed with this.

Similarly, 90 percent of citizens stated that dissatisfaction exists because the political leadership protects the corrupt. Only 6.1 percent disagreed with this. The study showed that 93 percent of citizens hold the view that those in government protect their close associates without taking action against them. Likewise, 93.3 percent of citizens hold the view that there is collusion among political parties in major corruption cases.

... ...

Democracy in danger due to non-transparent parties

- Dinesh Thapaliya, Former Chief Election Commissioner

Political parties submit two types of income and expenditure details to the Election Commission. One is the annual report for each year, and the other is the proportional representation system election expense statement. For the direct election system, each candidate submits the details of the expenses they incurred to the Commission.

What is the condition of the audit reports submitted by the parties? We have had them audited by the Auditor General's Office for the past three years to check. Upon review, it was found that the details submitted were unbelievable, and were provided merely as a formality because the law requires it. The parties' expenses appear to be highly disorganized, unrealistic, and the methods used to record expense details are also inconsistent.

How much money did a political party carry forward from the previous year in a fiscal year? Does the income get added and rolled over? How much did it collect in donations throughout the year? It might have also generated its own income. It collects levies from its members. The details shown in this manner are not transparent.

To hold a public assembly in Kathmandu, a political party might bring 10 to 20 thousand people. They are not usually from Kathmandu. They are brought from outside in dozens of vehicles with banners attached. Those vehicles must need fuel. To organize any event in Kathmandu, it costs more than 10 million rupees. There are flags, banners, and rallies. But their annual record of collected donations is only about 10 to 15 million rupees.

A party does not hold just one public assembly in a year. They hold district conventions. Central-level leaders go and deliver speeches. There are expenses incurred when central-level leaders are invited to speak, when party workers are gathered, when a stage is prepared, and when flags and banners are displayed. Then there are party conventions. How much is spent on conventions? Does that not fall under political expenses?

Therefore, not only are the parties' expenses unrealistic, but 90 percent of their income and expenditure are not reflected in their reports. Only around 10 percent seems somewhat plausible. How much money came in? How much was spent? Even the political parties themselves do not know.

What should happen is that the details of how much income was generated and how much was spent should be passed by the party's Central Committee. A proper audit should be conducted. Who gave how much donation to the party? The report should come with the names of the donors, but that is also missing. The law gives the Commission the authority to take action if someone provides unexpected assistance. But if there are no details on who provided the assistance, what action can be taken?

The law has tied the hands of the Election Commission. When it comes to the non-transparency of political parties and their expenditure, truly speaking, in the context of financial good governance, the condition of all political parties is extremely dire.

The expenditure during elections and the annual income and expenditure are within the limits set by the Election Commission. We can't really do anything. But when speaking outside, it is a different matter. I have even heard that some candidates manage to acquire land and housing by spending the money they spontaneously received for election expenses. They actually profit. The expenses submitted to us, however, are within the limit. We have instructed that candidates and parties must conduct transactions through the banking system, must be audited, and must make their expenditure and income public. We took minor action against those who didn't make it public, but a case was filed in court.

Currently, the biggest challenge to democracy is the lack of transparency in the donations raised by political parties and candidates during elections, their expenditure details, and the expenditure of what we call 'black money', undisclosed funds, and the situation is such that we can assume that political parties and elections are the very place where this money is spent.

It is stated that the parties' expense details should be audited by a registered auditor. However, looking at the reports, the question arises whether this even counts as an audit. We even wrote to the Auditor General's Office to monitor the auditors who audit the political parties. Shouldn't the auditor properly examine the income and expenditure that happens within the party? Simply marking the accounts with a green pen is certainly not auditing.

The Commission has raised questions where it had suspicions. It is not that the Commission is perfect and the parties are wrong. We also have our limitations. Five individuals from the central committee of any party travel across the country, sit with workers, discuss, and run campaigns. The report comes out as if the expenses incurred by these five leaders and the expenses incurred by the party are different. What do they travel in? Do planes fly them for free? Do cars not need fuel, but run on water? Shouldn't all these expenses be reflected in the party's financial report?

Building a stage for a wedding or a sacred thread ceremony costs 100,000 rupees. Buying a single garland or shawl (khada) costs 200 rupees. How many garlands and shawls are used in a single event? Where does the money for the expenses come from? Is that not an expense? They should simply make the expenses public and hold the events! If their own expenditure is opaque and disorganized, how will they run a systematic and transparent government? The question has been raised.

If the parties do not improve themselves, we cannot fix the system. The biggest challenge to democracy right now is that if democracy is consumed by anything, or if it runs into trouble anywhere, it will be due to the expenditures of the parties and candidates. The misuse of power and resources has put democracy in danger.

(Based on a conversation with Dinesh Thapaliya, the former Chief Election Commissioner.)

Please adhere to our republishing policy if you'd like to republish this story. You can find the guidelines here.